Tracking liquid assets: Groundswell creates Web-based water maps

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Agribusiness Topic

- Stephen Nellis Author

By Stephen Nellis Friday, November 1st, 2013

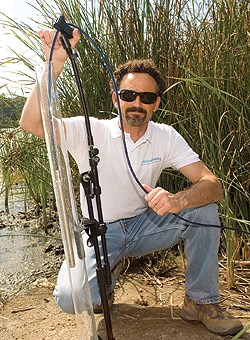

Groundswell Technologies founder Mark Kram. The company makes Web-based software that can intergrate data from any source and generate “heat maps” of water supply or contamination on demand. (Business Times file photo)

The fate of agribusiness in Paso Robles and Santa Maria hinges on groundwater rules that will be developed over the next few years.

The bad news for businesses is that vineyards in Paso Robles could face limits on how much groundwater they can draw, and Santa Maria farmers might have to pay to clean up drinking wells contaminated with fertilizer runoff. The good news is that the technology for real-time monitoring and modeling of groundwater that you can view on iPhone is available to consultants for all sides.

Santa Barbara-based Groundswell Technologies makes Web-based software that can integrate data from any source — whether it’s a cutting-edge sensor connected via satellites or historical records — and generate “heat maps” of water supply or contamination on demand. The key is leveraging powerful computers in the cloud to handle lots of data and generate reports that used to take weeks in a matter of seconds.

Founder Mark Kram, who obtained a doctorate at UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, said the tool is designed to help consultants deal with location-based mapping data from a variety of sources in a more efficient way, whether they’re working with government regulators or private businesses or landowners.

“We’re really a software company that implements all these technologies,” Kram said. “We are sensor neutral.”

While Kram may not be a household name in the region, he is well-known in environmental regulation and remediation circles. The software to run automated sensor networks that can provide a continuous picture of what’s happening underground could be a game changer. That earned Kram the 2011 Technology Awards from the National Groundwater Association. That year he also published a paper based on research in Kuwait, where houses were exploding and officials wanted to know why. It turned out that underground methane deposits were shifting and changing along with barometric pressure. It’s a finding that wouldn’t have been possible without software-enabled sensor networks.

“We discovered that when high pressure moves in, air gets forced into the ground and displaces the methane,” Kram said. “The earth essentially breathes in and out. That’s huge.”

In the Tri-Counties, the technology could drastically influence the debate in two critical agricultural regions. In Paso Robles, where groundwater draws have never been consistently monitored despite the area’s booming growth in both urban population and wineries, competing groups are vying to shape a potential groundwater management district.

In Santa Maria, farmers are facing the first requirements to monitor drinking and irrigation wells for nitrates and report their fertilizer use.

In both debates, Groundswell’s modeling of the relevant data would provide unprecedented insight to businesses, regulators and the public.

“All the data that’s been collected, even if it’s just lab data, we can plug that into our system and generate a playback loop,” Kram said. “It gives the decision makers more of an intuitive feel for what’s happening over time. You break it down to where you don’t have to have Ph.D. in groundwater or engineering.”

Kram is careful to point out that the models generated aren’t the final say — rather, they are a sort of “first cut” that would point regulators or consultants to anomalies that require deeper inspection.

But the key is that it makes viewing the changes between any two points in time very easy. “Within three seconds, you can select any time step you’re interested in,” Kram said.

So far in water fights, monitoring and public reporting of data have been key grinding points between regulators and businesses. In Santa Maria, farmers fought against publicly reporting individual well testing results. Monitoring of individual well pumping in Paso Robles is also likely to be a sticking point as any groundwater plan is hashed out.

But in the long run, if limited water supplies are going to be managed sustainably and equitably, better data is key. And the technology is well within reach, Kram said.

In Mexico, for example, all water extraction wells have wireless monitoring that tells scientists in the capital how much water is being drawn and what the basin levels are. “Mexico is so far ahead of the U.S. in terms of water supply management that it’s embarrassing,” Kram said.