Spilling the beans on Ventura County’s lima legacy

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Agribusiness Topic

- Henry Dubroff Author

By Henry Dubroff Friday, May 2nd, 2014

Threshing lima beans at Goodyear Ranch in Somis in 1910. For more than half a century, the drought-resistant lima bean was Ventura County’s top crop. (photo courtesy of the Museum of Ventura County)

On a fine spring day in the early 1870s, a Santa Barbara farmer strode the planks of the brand-spanking-new Stearns Wharf, at that time a marvel of innovation in commerce. He encountered a stevedore carrying a tall, leafy plant off a ship just arrived from South America. A brief conversation followed.

“What do you call that?” asked the farmer.

“A Lima bean,” said the dockworker, mispronouncing the name of the Peruvian city, perhaps because he was not a native English speaker.

And that, according to many accounts, was how the lima bean, a plant that dominated agriculture on Ventura County’s coastal plain for nearly a century, arrived in North America. After Henry Lewis, a Carpinteria farmer who was perhaps the gentleman on the wharf, and the Burpee company refined the bean plant, it proved a worthy cash crop. A century ago, about 75 percent of the world’s lima bean production came from Ventura County. Fortunes were made up and down the California coast.

In the 21st Century, the rise and decline of the lima bean holds important lessons. After all, the lima bean’s principal successor, the strawberry, has now seen a run of almost 50 years as a top crop. But just as the arrival of irrigation systems and changing consumer taste ended the lima’s reign, the drought and the emergence of new specialty crops is putting pressure on strawberry growers.

For museum curator Anne Gaumlich, the stories of Ventura County’s bean-growing families were timely and compelling. Recognizing that many of the children who grew up driving tractors and running threshing machines were now in their 70s and 80s, she decided to depict Ventura County’s decades as the bean capital of the world through the tales of families who tilled its soil.

The exhibit “Growing Up Growing Beans: Remembering Ventura County’s Limas” will run through mid-September at the Museum of Ventura County’s Agricultural Museum in Santa Paula. On May 8 at 2 p.m., the public is slated to share memories of the lima bean’s glory days at an informal talk at the museum.

And glory days they were. Beans were planted in spring and irrigated only by seasonal rain. The coastal fog and occasional summer drizzles did the rest, producing an abundant harvest most years without irrigation. The easterly fall winds helped dry the beans after they were stacked in wind rows.

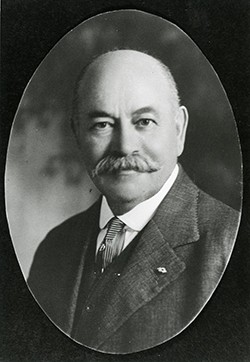

Back in the day, the lima bean fields of coastal California fed a hungry nation, helped the Allies win World War I by providing cheap protein to the troops in Europe, and created vast fortunes. Achille Levy, founder of The Bank of A. Levy, was principally a lima bean financier, broker and marketer. In October 1890 he shipped 22 railcar loads of Limas to Chicago, each car emblazoned with his name. The Midwest newspapers dubbed him the “The Bean King.”

A walk through the agricultural museum’s exhibit reveals limas were so important to Ventura County that it built a pavilion dedicated to them and sent it to the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Lima bean plants, not grape vines, are the leafy adornments that grace the original Ventura County Courthouse, now Ventura’s City Hall on Poli Street.

Gathering memories

Lima beans are hauled in sacks in Oxnard, circa 1920. (photo courtesy of the Museum of Ventura County)

Gaumlich isn’t quite as sure as some that the origins of the lima bean can precisely be pointed to that apocryphal sunny day on Stearns Wharf. But she does credit Lewis, for whom Lewis Road is named, and Burpee with developing a lima bean seed that would flourish on the California coast without the need for additional irrigation.

And she thinks the story of Levy, his landmark Bank of A. Levy and his gift for marketing are so integral to Ventura County’s success that she brought a recreated conversation with his wife Lucy to the museum a few weeks ago. The conversation helped kick off the bean exhibit by recounting how Lucy’s life in Paris changed when the handsome young merchant from California convinced her to join him on the Oxnard plain.

“Many, many families did well in agriculture and kept at it as long as they could,” Gaumlich told me in a phone interview. She has spent a lot of time locating the remnants of Ventura County’s bean industry.

One of the original bean warehouses is the home of the agricultural museum; another is a pallet factory on Pleasant Valley Road in Camarillo.

In addition to collecting hundreds of photos from the bean fields, she’s gathering up plenty of memories. Children of wealthy farmers learned the value of work: By age 11 many knew how to drive a tractor or how to operate a thresher. They witnessed winds strong enough to blow down rows of stacked beans and fires fierce enough to burn a crop to a crisp. Sugar beet farming took off early in the 20th century and vied for the top spot with limas, but the bean farmers prevailed for decades.

Lima decline

Achille Levy, founder of The Bank of A. Levy, was principally a lima bean financier, broker and marketer. (photo courtesy of the Museum of Ventura County)

By the 1950s, Ventura County’s lima bean farmers began to make a big shift from dried white beans to green Fordhook varieties that could be shipped frozen to newly emergent supermarket chains. In the 1970s, demand soared for new irrigated crops, including strawberries, and the great run of limas was coming to an end.

“For 100 years, it was a big important crop and then almost overnight, it was gone,” Gaumlich said. The growth of Ventura County cities coupled with demand for housing from Naval Base Ventura County contributed to the squeeze on farmers, she said.

“People became very good at farming,” she said. “As soon as the market changed they had to sell or find a different crop.”

Farmers had to make a choice: They could move to Northern California, where land was cheaper, and continue bean farming, or stay on the Central Coast and try their hand at growing new crops.

Gaumlich thinks the lessons of the current drought could be as big a game changer for Ventura County farmers as the transition from beans to berries was half a century ago. A record drought, combined with pressure from environmentalists and a growing population, is going to put a strain on farmers. “Things change but you don’t always know what’s next. You have to be smart or you just go broke,” she said.

But Gaumlich is an optimist over the long run. “Ventura County will always be a good place to farm because of the climate and the soil.”