Our view: Monetary policy shouldn’t be only game in town

IWhen President Ronald Reagan cut taxes in the 1980s, the national debt was 30 percent of GDP.

Even those tax cuts were partially reversed amid rising deficits and, by the late 1990s, the U.S. Treasury was running a rare surplus.

Today, after large tax cuts in the early 2000s, spending for wars and recession recovery and tax cuts again in 2017, debt is 80 percent of GDP and rising.

With the Treasury about to reach the legal debt limit, a bipartisan deal was struck in July that leaves tax cuts and spending plans largely intact — with deficits rising for years to come.

That makes us heavily dependent on monetary policy that preserves today’s ultra-low interest rates to fund rising debt and stabilize markets. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has called monetary policy “the main game in town if not the only game in town.”

Writing for the website “Project Syndicate,” UC Santa Barbara Professor Benjamin Jerry Cohen, a leading expert in political economics, has suggested an alternative path. He proposes the creation of a “Fiscal Fed,” a policy making body along the lines of the Federal Reserve that would have broad authority over some aspects of fiscal policy.

The “Fiscal Fed” is an attempt to avoid a death spiral of fiscal irresponsibility by the political class. As proposed by Cohen, the Fiscal Fed would have a professional staff. It would have limited powers to adjust payroll taxes, transfers and make “timely adjustments to the government’s revenues in response to changing economic conditions.” It would leave to Congress the prioritization of spending and would be subject to congressional oversight.

The current political environment doesn’t bode well for the creation of a Fiscal Fed anytime soon. But Cohen is thinking longer term, and it is worth noting that the need for a U.S. central bank was debated for decades before the Federal Reserve System was created a century ago.

What Cohen has perceived correctly is that if the U.S. dollar is going to remain the world’s reserve currency, then fiscal policy will need some steering mechanism and guarantees that $22 trillion in debt will be backed by the “full faith and credit” of the U.S. Treasury.

Over the long run, providing a framework for U.S. fiscal policy may be the best way to preserve our complex and highly globalized economic system.

FIGHTING FOR CONTROL OF PG&E

The battle for the future of PG&E is coming to a head in federal bankruptcy court.

On the one side are a handful of hedge funds that hold billions of dollars in PG&E debt and want to control the giant utility’s future. In opposition are current managers and shareholders who are reluctant to cede control.

Caught in the middle are utilities regulators and the administration of Gov. Gavin Newsom. Newsom and regulators have asked for a two-week time out in the proceedings to sort out how future ownership of PG&E will affect consumers. Recent legislation provides billions in relief for state utilities, which could create a windfall for whoever winds up owning the utility.

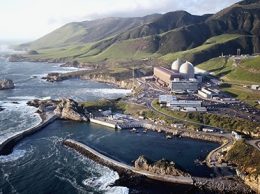

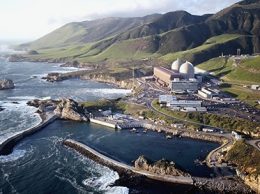

PG&E provides electric power to San Luis Obispo and northern Santa Barbara counties and owns the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant, a major employer that’s slated to be shut down in the middle of the next decade.

There is a lot at stake for the region in who finally owns PG&E.